The charity changing the lives of female drug addicts in Nepal

The charity changing the lives of female drug addicts in Nepal

Life is tough for women in conservative Nepal. Even more so if you are a drug addict looking for help traditionally available only to men

The abnormality of Parina Subba Limbu’s life is apparent as soon as you visit the headquarters of Dristi Nepal, the charity she founded for drug-addicted women in Kathmandu, Nepal.

The house, which is in the consular district of the city, looks like a handsome three-storey suburban villa with bougainvillaea growing in the front garden. But walk in and you meet a woman being treated for an abscess from injecting heroin into her groin. Another, found lying in a nearby doorway, is having a pregnancy test. Upstairs, Devi, a beautiful 19-year-old with a baby son, is explaining how sniffing Dendrite, a shoe adhesive, is ideal when you live on the streets, because it “kills your hunger for two weeks and you don’t feel pain, cold, anything at all”.

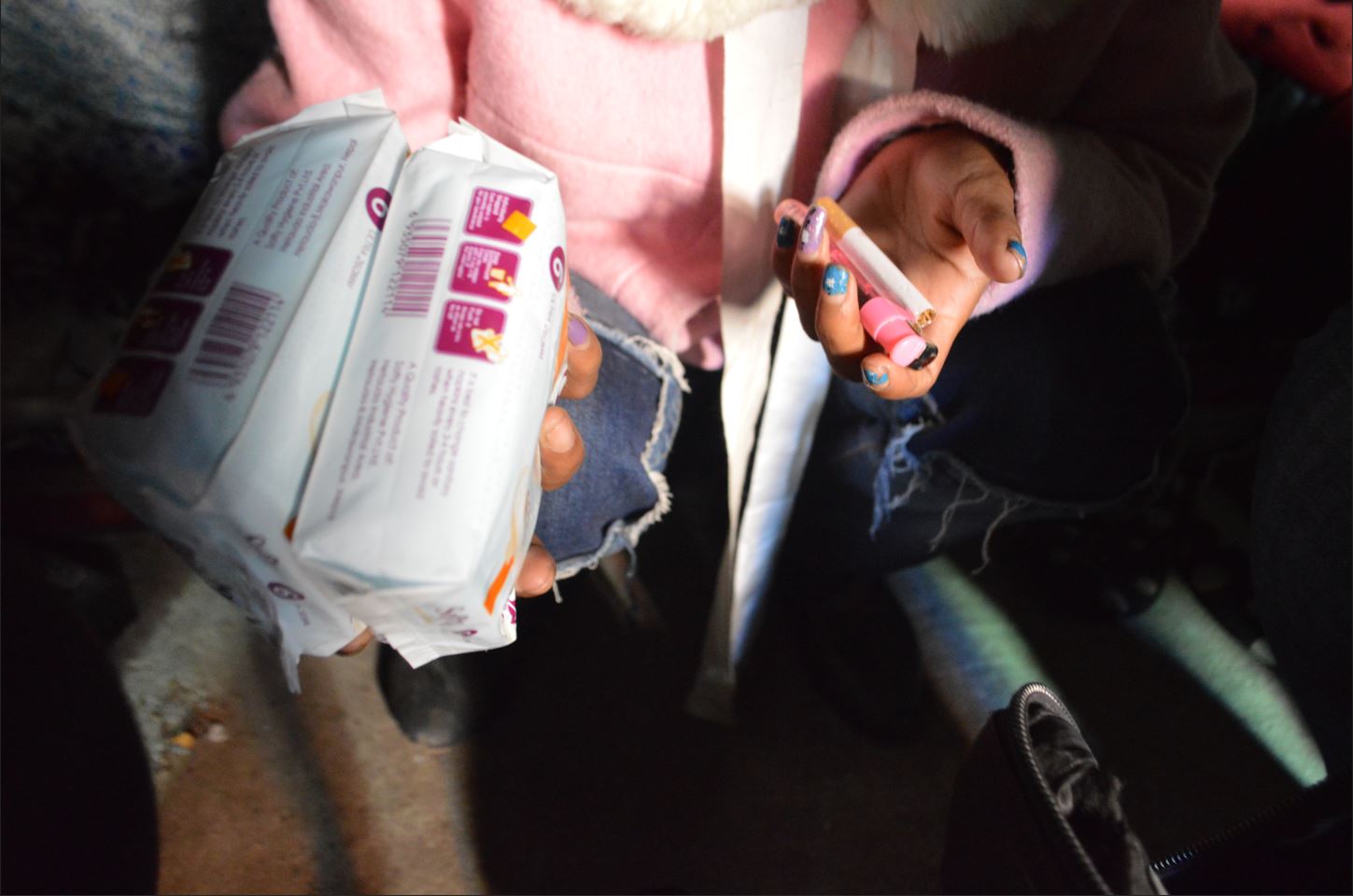

Limbu is 33 years old, is less than 5ft tall and has a worldly confident air. She is also a recovering heroin addict, who smokes like a fiend and has 10 tattoos (a crying dolphin has been changed to a smiling dolphin to mark her sobriety). In Dristi everyone uses her first name when talking about her. Or else they’ll refer to her affectionately as daili – which means “shorty and plumpy like a potato”.

Limbu’s work at Dristi may be helping the lives of vulnerable women, but it has made her something of a pariah in her native Kathmandu. Nepal is a country with deep-rooted traditions. “We live in a patriarchal society, which continues to influence not just women’s status and value but also the extent of treatment and care,” she says.

Parina Subba Limbu, an ex drug addict who is the founder of Dristi Nepal (Anna Huix)

Women in Nepal have a central role in managing their households, but do not have much say in public life. Their reasons for taking drugs are mostly the same as men’s and vary from adolescent experimentation, imitation and rebellion to escape (from poverty, loneliness, abusive relationships). But once addicted, women are condemned and “suffer stigma and discrimination”, says Limbu.

Over the past 20 years or so there has been a sharp increase in drug-taking in Nepal. Of more than 91,000 drug users in the country, 6,330 are women, according to the Central Bureau of Statistics, Government of Nepal. But their number is rising fast and has doubled since 2007. Treatment is urgently needed but drug use deepens the inequalities between the sexes.

“Women tend to fall through the cracks in male drug programmes,” says a report from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Women are sidelined in treatment centres, charged inflated prices for condoms, blackmailed into having sex by police. Families may also hide the problem for fear of scaring off potential husbands, particularly as women sometimes turn to prostitution to support their habit.

“Men can go to drop-in centres [DICs] and ask for condoms and get a needle and syringe, but females are not supposed to go into DICs because you are not supposed to be taking drugs in the first place,” says Srijanna Rai, a recovering addict who now works at Dristi. When female addicts suffer from related health problems – many are HIV positive – getting medical help can be difficult. Dristi employs Bobby Singh, a young Nepali, to accompany the women to hospital, as the doctors are more likely to listen to a man.

The prejudice against women addicts is why Dristi has moved eight times in as many years. “Every time a landlord finds out who we work with – boom – we’re out the door,” Limbu says. “Last year we had a really nice landlord. He totally understood and even admitted he was an alcoholic. I was helping him but then one day he said, ‘I’m sorry, my family say you must go.’”

Nepal was almost a closed country until 1950. The few Westerners who visited Kathmandu would have to walk in by a steep and rocky path, a journey that took days. Then the city’s airport opened and by the 1970s the hippies hit town, drawn by the low cost of almost everything. They settled on a rundown street, nicknamed Freak Street, near the city’s ancient temples, and immersed themselves in drugs and mysticism.

Leeza Lama, a counsellor and outreach worker at Dristi Nepal (Anna Huix)

Forty years on, most of these early adventurers have long departed, though a few of them have gone into the trekking business. But the door they pushed open admitted other foreigners – tourists, aid workers – who challenged old habits. Now MTV and Korean fashion have arrived in the Kathmandu Valley. The result is a strange mishmash of medieval traditions and the modern world.

Our driver, fighting his way through the choking traffic of Kathmandu, slowed down to avoid a sacred cow sitting in the centre of a narrow street. Women in traditional kurtas and churidars mingle with teenagers in tight jeans and teetering platforms. Houses with cable television are occupied by people locked into an ancient and rigid caste system. Similar to that of India, with four principal castes, technically this has been abolished but it is still observed. For all its changes, Nepal is essentially backward-looking, and for women this not-quite-modern country has a dark side.

READ:

Leeza Lama, 24, a delicate child-woman with pale skin (she is also known as Barbie or Humming-bird – “even smaller, even sweeter”), is a counsellor and outreach worker at Dristi. She is showing me the hot spots of Kathmandu. We stop in Durbar Square outside a Hindu temple, in the west of the city. There are tourists in hiking trousers, stallholders selling tea. One man walks by with a sofa strapped to his back. The air smells of incense. We walk down some concrete steps to the mud bank of the Bagmati river. There is rubble and excrement-splattered rubbish. Lama points out a white house opposite where some women addicts live, and a group of feral children huddle under a bridge. “I was standing here when I injected for the first time,” she says.

Lama had fallen in with a “bad crowd” at school. She was an addict for seven years, and has been clean for two. Her favourite drugs were an antihistamine called Avil, the tranquillizer diazepam and Phenergan (used to treat motion sickness), which she would grind down and inject. According to the UNODC report, women in Nepal “often choose to inject medically available pharmaceuticals with a high potential for addiction, overdose and vein damage”. Lama shows me a figure of a god tucked into a niche in the wall: Lakshmi, the Hindu goddess of wealth and prosperity. This is where she would hide her syringes. “It’s difficult to come back,” she says. “I feel sad, guilty.”

Dristi Nepal came about when Lee FitzGerald, the executive director of a group of addiction treatment centres in America, was invited to run a workshop for women in a Kathmandu hotel in 2006. A former model and head of an advertising agency, FitzGerald had been a serious addict for 14 years. At the time of the conference she had been clean for six years. It was her conviction that the Narcotics Anonymous 12-step programme worked, and she toured the world encouraging other addicts on to it.

But what she discovered when she arrived in Kathmandu profoundly shocked her. “The men had the NA meetings. The women had nothing,” she recalls. “The NA international directory [which lists meetings all over the world] didn’t even include women’s meetings.”

The 16 or so women who turned up that day – mostly young and quite heavy drug users – needed help. But there was no institution or mechanism in place. It didn’t seem fair. But FitzGerald’s young translator said she had an idea. “She said she was going to fight the stigma and just needed someone to help her,” FitzGerald recalls. The translator was Parina Subba Limbu.

Limbu grew up in Dharan in eastern Nepal, near the border with India. Though not wealthy – her father works in hospitality; her mother was a healthcare assistant – her parents did invest in her education. They sent her to a local co-ed English boarding-school when she was three, where she proved to be “clever and outspoken”.

As she got older and more rebellious she started taking drugs – mostly marijuana and prescription pills. When she was 15 she fell in love with an older boy who also took drugs. They ran away and she ended up living with his parents, who treated her like a servant because she was of a lower caste. At 17 she became pregnant and was forced to have an abortion. Abandoned by her boyfriend and disowned by her own family, she plunged into an ever darker world. She took heroin, lay senseless on casino snooker tables, suffered the worst degradations – “emotionally, physically, you get used”. She is determined her three-year-old son will never know anything of the memories that burden her.

Despite being in a state of almost constant intoxication, she managed to work as a marketing consultant and translator. In 2004 she met her future partner, a tattoo artist and recovering addict. “I knew I had to stop.” She went to a private rehabilitation centre. “Men would look at you. Tut, tut, tut,” she says. This only made her more determined. “There are so many women struggling with violence, drugs and this bloody caste system, I felt I had to do something.” When she met FitzGerald at the convention in 2006 she had been clean for a year.

Srijanna Rai, 24, another of Dristi Nepal's success stories (Anna Huix)

Dristi, which translates as “women”, opened that year in a room behind a shopfront near Swayambhunath, the “Monkey Temple” in the west of the city. FitzGerald and Limbu had to invent a cover so that the landlord would agree to rent them a room. They told him they wanted to open a candle-making workshop. A year later Dristi expanded to a second office in Dharan and now helps about 100 women a year. With 10 paid staff (and numerous volunteers), it costs about £20,000 a year to run. Funding comes from agencies such as the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Lee FitzGerald herself and one-off donations from individuals.

Last October Gavin Cooper, a British businessman, was at a convention in Florida for the addiction treatment industry. As well as working in the field of addiction – Cooper runs Landre Capital, which owns the One40 network of treatment centres in Britain – he is a recovering addict. There were various speakers at the convention and one in particular “brought tears to my eyes”, he recalls. It was Lee FitzGerald talking about Dristi. “She spoke so passionately about it. As a man I can walk into any fellowship meeting in the world, and when I heard that these women were bullied, segregated or pushed out, I decided I had to do something to help.”

That night Cooper gave FitzGerald $3,000. (“In cash!” she says.) Cooper now publicises Dristi in Britain and has organised a fundraising dinner and auction that will take place in London, on 6 May. “Our aim is to raise enough money to buy a permanent base, so Parina and the girls don’t keep getting moved on,” he says.

Dristi is growing. There is a drop-in centre, and a health clinic with a nurse five days a week. On the upper floors, which are open only to those who are drug-free, there is a brightly painted bedroom with five beds where women can stay for up to 28 days. On the wall is a large white notice with the heading daily routine with lists of activities: 7.20am-7.50am meditation (yoga); 9am-10am shower time; 10am-11am counselling session etc. There is also a “skill development” room where the women make candles, baskets, key rings, purses and iPad covers to sell. Dristi offers counselling, pregnancy testing and condoms, and plans to introduce a 28-day drug-withdrawal programme.

Dolmo Ghalan, 20, sociable, pretty, with cool-girl clothes, started taking drugs at the age of 12. “There was a circle that used to smoke and I always refused,” she explains. But gradually she became embarrassed about not joining in.

“I started smoking cigarettes, then marijuana, then brown sugar [heroin]. Because I am from a poor family someone from Germany was sponsoring me through high school.” Her studies suffered and she was expelled. “My school informed me that my sponsor wasn’t going to sponsor me anymore. I cried a lot, because from my childhood I’ve always thought I’d be an air-hostess and for that you have to study hard.”

The guilt at having let everyone down made her sink deeper. “Yes, of course,” she replies, when I ask if she had sex for drugs. “I have told you my economic situation.” Thanks to Dristi she has been drug-free for two years and the charity is now paying for her studies – 12 months in all, plus an admission fee. She has accepted that she will never be an air-hostess – “My tattoos,” she explains – and her ambition now is to work in tourism.

Bikens Nembang, an ex addict who is now a volunteer at the charity (Anna Huix)

Bikens Nembang, 26, stylish in cropped leather jacket and suede boots, is absorbed in a YouTube clip of Beyoncé on a friend’s iPad. She is the daughter of a former Gurkha who moved to Britain when Nembang was small. Soon after, her mother died, and Nembang was brought up by her brother and his wife. Tattooed around her neck are the words 'no matter how far we are, we are always together', done when she was still with her now estranged husband, who introduced her to drugs when she was 14. On the nape of her neck is the name of their 11-year-old son, Manahang, whom she last saw three years ago.

“My son is with his dad and his parents and they won’t give him to me,” she explains. A scar on her hand is from when she smashed a window in the rehab clinic on her first day without drugs in seven years. She hasn’t taken any drugs for eight months but clearly still feels anxious. “Very dangerous dream,” she writes on her Facebook page. “Started using… god wat da hell is this… toooooo scared… god plz dont let it b again.” “I feel better,” she tells me, “but so sad. If we are without drugs we feel the pain. My son… it makes me feel very sad. It’s very difficult to face people like this.”

Nembang lives in Dharan but is working as a volunteer for Dristi, because Limbu wants to keep her close. “They think if I’m not involved here I will go back to drugs, so I’m here to keep me safe.” She adds, “My father, sister, sister-in-law, two brothers, stepmother, cousin rejected me. I am dead for them. But Parina takes care of me. I never had any love from my family, never knew the feeling of mother love. But I feel it from her.” And with that, she lights a cigarette and goes back to watching Beyoncé.