Established in 2006, Dristi Nepal is a peer-led harm reduction organisation for women who use drugs, those living with HIV and sex workers. Since April 2018, the organisation has been running a needle and syringe program for women who inject drugs in major centres around Kathmandu.

Dristi’s broader mandate is to promote the rights of women who use drugs, prevent gender-based violence, counter the stigma and discrimination experienced by these women and, of late, it has extended to assisting in the economic empowerment of marginalised women as well.

Operating such an organisation in a country like Nepal is no mean feat, as while gender equity and antidiscrimination exists in law, on the ground it can be a very different experience, and when it comes to women who develop drug issues, loved ones can simply abandon or punish them.

Over its time in operation, Dristi has helped hundreds of local women, it’s broadened awareness in the community to go beyond the zero-tolerance, failed “just say no” approach to illicit substances, and the South Asian organisation has been active on the international harm reduction scene.

Triumph over adversity

Parina Subba Limbu is the founder of the first women-centred drug user organisation in Nepal. And when you meet her, it’s apparent in her demeanour how she had the ability to transcend societal boundaries to establish a foundation that promotes the welfare of those others turn away from.

Speaking at a 27 September TEDx in the Kathmandu Valley city of Lalitpur, Limbu explained that she’s no stranger to adversity herself. The now 42-year-old single mother-of-one recalled that at the age of just 16, she moved into the family house of a man who abused her severely for six months.

This experience led Limbu into drug use, which eventually became problematic, while she also left her hometown to forge a life for herself in Kathmandu soon afterwards. And a chance encounter at 23, saw a woman from the US gift her the funds which she used to create Dristi Nepal.

“I didn’t want, and I still don’t want, to see any women go through what I have been through,” she told the TEDx crowd. “That is the only reason I started Dristi. And I didn’t start to talk about the story of my violence until I started earning money of my own.”

Economic empowerment

Three days following the speaking event, Dristi Nepal led a coalition of organisations in hosting a women-led marketplace, in which marginalised women – drug users, sex workers, those living with HIV and single mothers – were given the opportunity to showcase their grassroots businesses.

As she explained during her TEDx speech, Parina wasn’t able to properly address the harm from her past until she became financially independent, and she’s now come to realise that other women need to be assisted in achieving economic empowerment in order to resolve their own issues.

Sydney Criminal Lawyers sat down to speak with Dristi Nepal director Parina Subba Limbu about the plight of Nepali women who use drugs, the great disparity in funding when it comes to them, and how she’s eyeing off attending next year’s international harm reduction conference.

Dristi Nepal provides harm reduction services and rights advocacy to women who use drugs, as well as those living with HIV and sex workers in this country.

Parina, why is there a need for a harm reduction organisation, like Dristi, in Nepal that has a particular focus on women?

When we look at the social economic demographics of Nepal, the women’s rights movement and the support from government, women in general are left behind, so when it comes to women who use drugs, they’re far, far behind.

Then if you look at the funding dynamics, there isn’t much allocated to women who use drugs. So, the funding that’s being allocated is part of the national program. And that is one of the reasons that women who use drugs need our services.

But apart from that, when we talk about harm reduction, there are lots of women who are going through different complications in life, and this is one of the gateways to make women who use drugs aware of their rights and responsibilities in regard to health and human rights.

So, that’s one of the reasons that harm reduction services are playing a huge role in Nepal.

Dristi Nepal is a peer-led and run organisation that’s been operating since 2006. How important is it to have those with lived experience involved?

There have always been pros and cons. Having people with lived experience does bring difficulties because of a few factors, including their level of understanding, how they were brought up and their economic conditions.

These all matter when it comes to community engagement, organising and to how we operate, because there are lots of expectations, and this can be one of the biggest challenges in running an organisation with peers.

But, at the same time, there are good parts. When we have peers in roles, such as working in the field or delivering services, it’s good to have peer-to-peer connection, as it has always been one of the key factors to reach others and to understand them.

Fifty percent of working with peers is complicated, but at the same time, that other 50 percent contributes in a very big way.

When it comes to work, assessment and reaching out, it’s important to have peers. But when it comes to capacity-building or skills there’s a huge gap, even in their understanding of harm reduction.

I would say there’s still a need for more programs, not just service delivery. There should also be investment in educating peers to understand what exactly harm reduction is and what our rights are. And there is a need for investment in regard to this.

I’d also like to add my perspective from having run the organisation for such a long time, as there are politics in this country within the donor community and the NGOs, and there are disparities between men and women, which all hamper implementing harm reduction.

We have had lots of peers with us, who we were not able to make happy, as we don’t get any kind of support from donors, except for the needle access program. If there is a woman having SRH (sexual and reproductive health) problems, there’s no money.

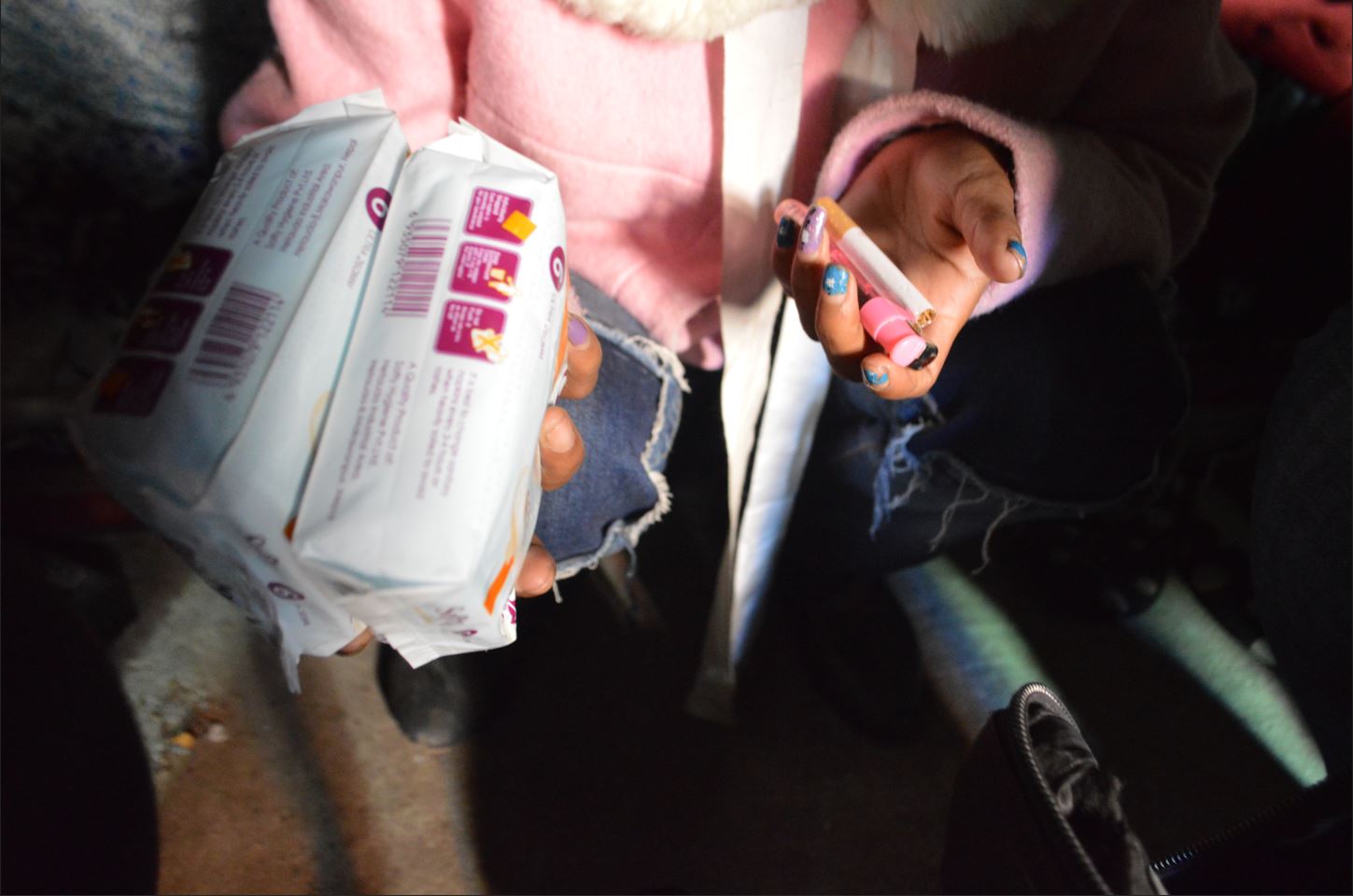

But when peers come, they’re not always coming just to get needles and syringes, because, as women, they have so many other issues that need to be addressed.

Harm reduction is not just needle and syringes. There are other components, such as domestic violence, human rights – all these things.

But, unfortunately, in Nepal, and all over the world, we’re not addressing these other components.

That’s where we get into conflict with our peers as well. This is my perspective as a peer organiser, who has been doing this for the last 15 to 16 years.

You’ve just mentioned needle and syringe programs. In Australia, NSPs were rolled out nationwide in the mid to late 80s in response to the HIV/AIDS crisis. Yet, more recent attempts to establish drug checking services have faced great political resistance.

What sort of harm reduction measures are available in Nepal?

A whole chunk of money here is going to the needle exchange program, and then next it goes to HIV testing programs.

Now they have started self-testing or community-led testing all over Nepal under harm reduction programs.

But these are very general and simple things. When it comes to women, it’s more complicated. They’ve got children. They get beaten up by their partners. They’re subjected to violence. They do sex work.

Imagine, when they need documents for their children, and they don’t have citizenship. They can’t even go to school. So, there are all these other things.

Dristi Nepal has been advocating around these issues, but, unfortunately, there’s never been the drastic change to do this in terms of harm reduction.

There is only HIV testing and peer-to-peer counselling. So, if you’re going through violence, they need to do one thing, or if they have an STI or HIV, they need to do another. But that is it.

When it comes to women and harm reduction, we need to understand that it’s going to take time because of the economic conditions, the society and the stigma.

The responsibilities of being a woman in Nepal are different. So, they’re not just drug users. They are mothers. They are daughters. They are partners. They are so many things, and this is totally forgotten.

This particular issue has never been addressed by any of the donors in Nepal. And I am sure, I haven’t seen donors around the world putting money into these broader programs for women.

You talk a lot about stigma and discrimination as being major hurdles when seeking to improve the lot of women who use drugs. Can you talk about why that’s the case?

There’s the maturity of the community. They’re still into abstinence programs. There is still a huge misunderstanding about what harm reduction is all about and what abstinence is all about.

When it comes to women who need to go to the rehabilitation centre, they can’t go because they don’t have money.

And when their parents know they’re using drugs, they would rather say, “Bye-bye. We can’t do anything for you. You chose to do it. So, you better wear it.” And that’s because we don’t have enough services here in Nepal for women.

It’s not only harm reduction. In general, we don’t know how many women are affected by drug use. Sure, there are estimates of 8,000 to 9,000 women. But I’m sure that’s not really the number.

So, when it comes to women it’s not only the drug use. They’re either kicked out of their home, or they go through violence with their families, their siblings or their partners. Not many women are actually supported.

This is one of the things that has to be looked at when we’re developing programs.

Also, there are huge gaps in regard to overlap issues. When a woman starts using drugs, the social responsibilities of being a woman are already there and apart from that, some of them are sex workers and some are living with HIV.

So, these overlap issues are never addressed in any of the programs.

There are no specific programs for women who use drugs who are also sex workers. So, it’s like putting one program in place for all woman, and it doesn’t matter whether you’re a sex worker or you’re HIV positive.

The stigma and discrimination were always there, are always there and will always be there.

Even in service settings run by the government, it’s always frustrating. I’ve been involved in initiatives, where I give my input and then contribute to make the handbook for the service providers, so that they don’t look at us like we’re aliens.

And the fear of stigma and discrimination is huge. This is the main point. Stigma and discrimination are always there, but the fear of being stigmatised is also creating a constraint to accessing the little services available in Nepal, especially for women.

There are ten men to every one woman accessing OST (opioid substitution therapy) services. Why? It’s the fear. They fear the stigma – of getting stigmatised. They fear it from the community itself.

When it comes to male drug users, unfortunately, even men who use drugs judge us. They think we are going to sleep with them.

Oh, really?

Yes. So many of them think, “Wow, she’s dangerous”, or they abuse us. That’s our fear.

I used to bring up this topic all the time and there are lots of men who don’t like me, because they think I’m talking bullshit.

But it’s true, otherwise there would have been lots of women accessing OST services. But now, at this point, no one is talking about this issue. It’s always pushed a little to the back.

So, would you say that if an average family in Nepal had a teenager who develops a drug dependency issue, that family would be more likely to support a son through that than a daughter?

Yes. Also, with families, there is a lack of awareness about harm reduction programs. The parents think one thing, “Let’s send them to rehab.” That’s the end. They just want to throw them there if they can afford it.

So, they’re not aware of harm reduction. That if a woman doesn’t want to quit, there are OST services, which they could access. It’s very hard, as they think methadone and buprenorphine are just a substitute.

And while, yes, they are a substitute, in the long run, they help people who use drugs. And parents are not understanding this, because there’s not enough investment in creating awareness on what it’s all about.

Last year, our outreach peer workers went to meet with some people who called about the needle exchange program. They went to the place but didn’t realise there was a police station nearby. The exchange was done, and the workers left.

Then after 10 minutes, the phone rang in our office. Someone from the police had called. They said that they’d found the syringes, and they wanted to know what it all was. The people there didn’t know what to do and even our outreach workers got scared.

So, I spoke to the police on the phone in a very low tone and I had to tell them what it was and if there was any problem, they could call us.

But this was about the national program. And in Nepal, this is what is happening with law enforcement.

We still lack so many things. And I’m not that proud that Nepal has a harm reduction program, because if it’s just to reduce HIV then it’s a failure.

We are not just here to reduce HIV. We need to work on human rights. We need to work on health rights. We need to work on other overlap issues, especially when it comes to women. But it hasn’t been happening here in Nepal.

So, that’s how I’d like to elaborate on stigma and discrimination when it comes to women.

Significant drug law reform has been taking place around the world over the last decade. This is especially so in the case of cannabis, but there’s also a trend towards drug decriminalisation.

How is this global shift being reflected in Nepal?

I would say that there have not been any changes at all. I’m sure there are some organisations getting funds to do policy reform or the decriminalisation thing. However, as a hardcore harm reduction activist, I would say no.

When it comes to decriminalisation and legalisation, they’re still fighting about it. Even the activists working in this field don’t understand the differences between legalisation and decriminalisation.

People misunderstand the whole process. Men and women are still being criminalised, even though there are measures in place.

If a person gets caught by police with five grams of hard drugs or some green, we can write a letter and go to the police. We say, “Okay, they’re a drug user. We can take care of them. We will take them into a rehabilitation centre.” That’s the format of the letter.

But we need to write that they will be put in rehabilitation. So, that’s an example of the power abstinence programs still have.

I’m not against that. However, as an activist, I would also like to intervene and say, “Hey, that drug user would like to do an OST program.” But nobody cares about that. All they want is the paper, and that’s it.

So, by force there are lots of things going on here. On social media, I can see lots of men going to rehabilitation. But there are only around six or seven rehabilitation centres for women in Nepal, whereas there are hundreds of rehabilitation centres for men.

Again, looking at harm reduction programs, there are hundreds for men, but for women, there are only four or five that I can count, and it’s because of the little amount of money.

You would be shocked. Our peer workers only get at max a hundred and fifty dollars a month for delivering services.

This has all been impacting legal reform on decriminalisation. So, I would say there has not been any significant changes. And I don’t think there has been any sort of changes in law.

Dristi is heading up a number of organisations in hosting a women-led marketplace tomorrow in an area of Kathmandu, which is all about showcasing women-run businesses to assist them in their own economic empowerment.

This is happening because, after years in the harm reduction space, you’ve come to the conclusion that economic independence is vital for women in dealing with issues such as drug dependency.

Can you elaborate on why that’s the case?

We became so dependent on donors, and not to say we don’t need donors, but there are so many issues for women who use drugs, such as having children, needing housing, as well as food. And this is apart from the needle syringe program.

So, what we realised is because we need other such programs for women, not just the needle program, and for many years we’ve been asking for funding, but no donors have been interested, so we thought, “Why not become self-sufficient?”

Donors don’t want to put money into these extra programs. They don’t want to support the children of women who use drugs. There are no proper housing schemes either from government or from donors.

We need to see beyond HIV. We need to see beyond harm reduction. And what we’ve realised, through doing surveys and analysis, is the poor economic conditions of women who use drugs and those living with HIV.

We are starting this as a pilot project, so that in the future we can make our own resources. It’s a tough thing to do, but I know that this will lead somewhere.

We are not saying that all women who use drugs, or those who are living with HIV, and have overlap issues, will be covered by this.

But this time five women will be and maybe next time ten will be, and then they’ll know responsibility.

In Nepal, we cannot run away from the reality that our government is not going to support us, and donors won’t fund these other issues.

So, it’s just us. And we want to start networking with other women’s groups, and talking about our issues, because the other women’s groups may not know about our other issues.

And we are lacking that. We don’t have many allies. We are in our bubble, and its high time we start making allies with people who would start talking out for us and being our voices.

We have done enough interventions, work and projects. This is the next challenge, because if our needs are not met, it is not going to help.

We need to strategise. We need more people to understand our issues and support us. So, this is something that’s going to be a long-term project, developing into the future.

And lastly, Parina, Dristi was presented with the 2014 Red Ribbon Award by UNAIDS at the 20th International AIDS Conference in Melbourne that year.

At present, you’re considering returning to that city next year to attend the Harm Reduction International 2023 conference.

So, why is it important that Dristi is there to represent Nepali women who use drugs?

Dristi Nepal has been represented at most of the international harm reduction conferences. All, except Malaysia. We missed that one.

But apart from that, Dristi Nepal has always been a part of the international harm reduction conference.

The reason that we want to go this time is that we need to change the strategy if we want to work with women who use drugs.

We cannot put all women who use drugs in one bucket: there are subgroups. There should be different approaches.

It is high time that we change the strategy and see through different lenses, not just from a harm reduction lens or a HIV perspective. Like I said, it’s not only needle exchange programs but there are other components to harm reduction.

What about capacity-building? What about economic empowerment? What about human rights? These are the things that need to be addressed.

So, we’re writing an abstract, and hopefully, we get selected. And if we get someone to donate and support us, we will definitely go and represent all women who use drugs, because I’m sure that we’re not any different from other countries.

Everywhere it’s the same. The only thing is we’re talking about this from this country, where we don’t have strong networking.

I know there is INPUD. There is WHRIN. There are networks for women. But the needs are still there, and the understanding is different.

At the last conference, we discussed white supremacy and how it’s even affecting harm reduction programs.

Who’s leading these programs affects the outcomes for everyone. And that’s why I want to go and represent Nepal.